Lifesaving chain of events: from an emergency call to help arriving on scene

We’re texting, calling, and messaging throughout the day. At the end of 2019, 5.2 billion people worldwide were subscribed to mobile phone services.[1] But the most important call we make may be one to request help from emergency services.

To make it possible for citizens to quickly get assistance, there is a complex system in place in each country. Although certain countries may share an emergency number – such as the European emergency number 112 – the organisation of emergency call-handling can differ significantly. How many organisations are involved? What is the role of the call-taker(s)? Who decides on the dispatch of resources?

In response to this complexity, EENA created 5 emergency call-handling models to simplify the different structures available across the globe. We can find out the major characteristics and main stages of the most common models worldwide. Shall we take a look?

First things first…

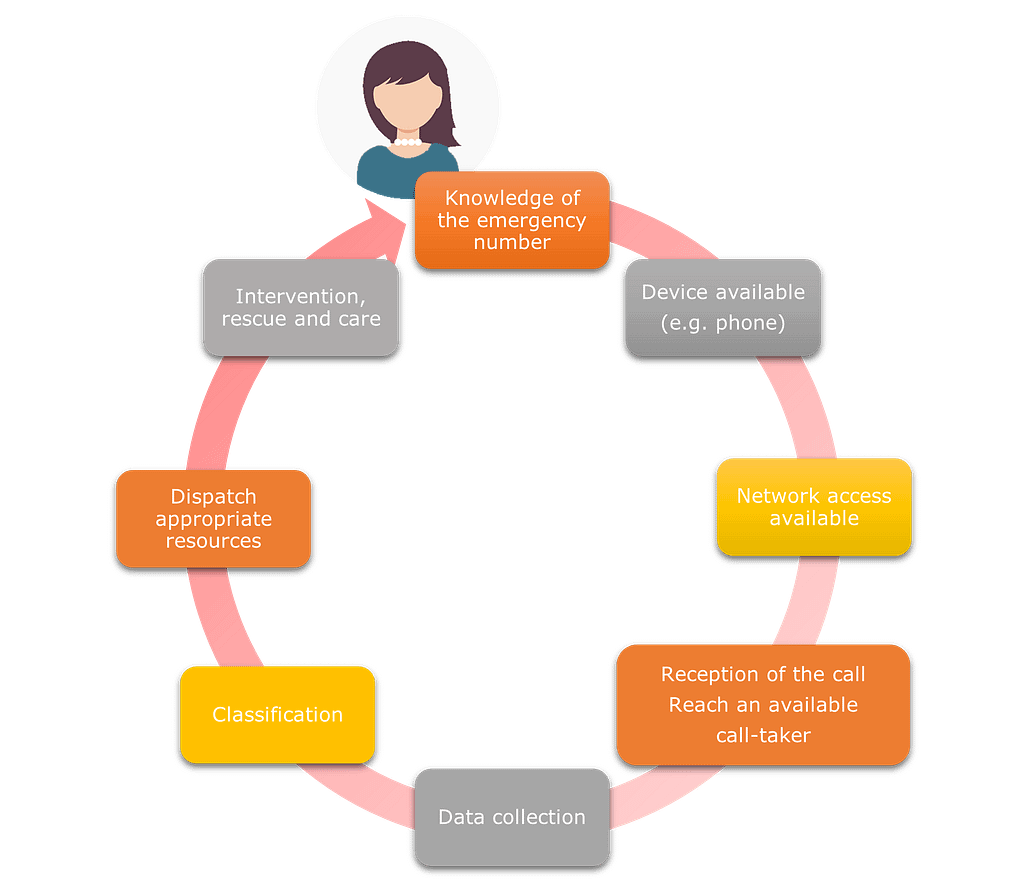

Let’s think about what’s involved in the emergency response chain. To connect with emergency services, not only do citizens need an available device and network access, but also knowledge of the emergency number. If all these elements are in place, the citizen can reach an emergency call-taker.

Our models refer to the next stages of the chain. Once the call is received, the data collection process begins; emergency services start to understand what is happening and where the citizen is. This information is decisive in classifying the call: how should the citizen be helped? Emergency services then proceed to dispatch resources to the scene, resulting in the intervention.

Model 1

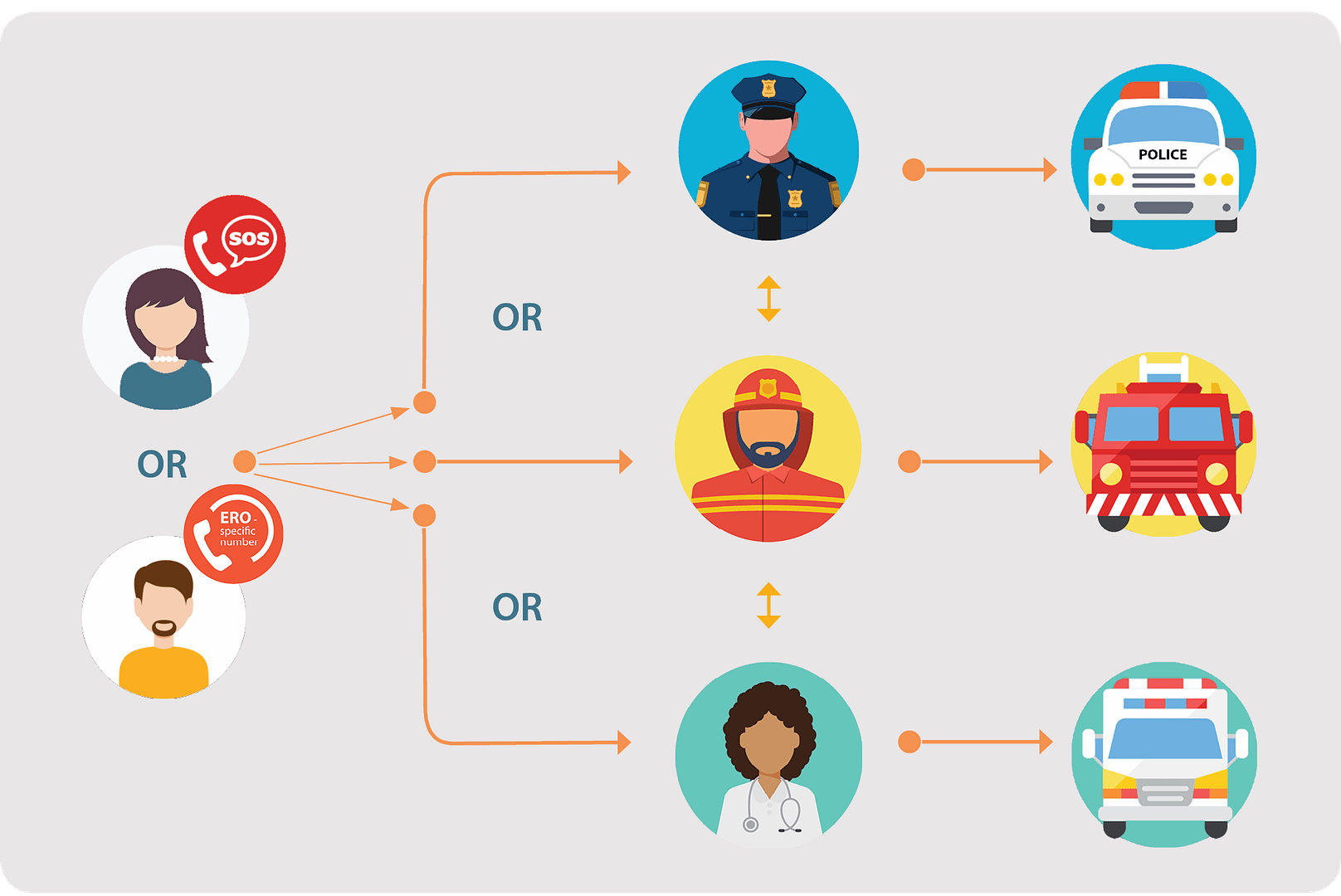

Some countries have several emergency numbers. As an example, in France, each service has a specific number and citizens can use the general European emergency number 112 too. In Model 1, the call is handled by the call-taker for the specific service dialled and calls to general emergency numbers (like 112) are handled by one designated service. The call-taker collects the data, classifies the call, and dispatches the resources to the scene. If the call-taker identifies that a different service is required, the call and the data are forwarded. You can find this model in Austria, France, and Germany. In Luxembourg, a variation of this model is in place, where the call-takers for each service are all in the same building, which can help improve coordination.

Model 2

Model 2 has two major differences to Model 1: there is only a general emergency number which people call to access all the services and there are two levels of organisation for call-handling. The call is first received by an independent organisation, which filters the calls. For instance, in the UK and Ireland, the first (stage 1) operator may ask ‘Which service do you require?’. Based on the answer, the call is forwarded to the correct service. The second operator (stage 2) will find out the details of the emergency and will dispatch resources.

Model 3

Model 3 looks similar to Model 2, I hear you say. You are right, but there is one important difference. In Model 3, the classification and data gathering are done by the first (stage 1) call-taker. The call-taker then makes a parallel dispatch to the relevant services, which send resources to the scene. We see this model in place in Romania.

Model 4

In this model, we again see the coexistence of a general emergency number (like 112) and national numbers for each specific service. In contrast to Model 1, the general number leads to an independent call centre, whereas the national numbers are routed directly to the relevant service. The general number follows Model 3, while the national numbers follow Model 1. This is the case in some regions of Spain.

Model 5

You made it all the way to Model 5! Here, all emergency calls are made to the general emergency number and they are handled by independent, civilian operators. They are highly trained because the same person is responsible for the collection of data, classification, and dispatch for all types of calls. In Finland, operators carry out a lengthy, intensive education before starting work.

These systems are put in place to ensure that emergency services are on hand as quickly and efficiently as possible when we need them. By understanding these models, we can also begin to comprehend the complex organisation and coordination that is required along the chain of emergency response.

Head over to our Emergency Call-Handling Service Chain Description document to read about the models in more detail. You’ll also find a handy decision tree to help you work out which model is in place in your country.

[1] GSMA, The Mobile Economy 2020: https://data.gsmaintelligence.com/api-web/v2/research-file-download?id=51249388&file=2915-260220-Mobile-Economy.pdf

Author: Rose Michael, former Knowledge Officer & DPO at EENA

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of EENA. Articles do not represent an endorsement by EENA of any organisation.

Share this blog post on: