NG112 implementation in Europe – Demystifying the ESInet and Next Generation Core Services

- March 27, 2024

- Categories: Uncategorized

Current emergency communication systems in Europe are primarily voice-based, but the transition to an all-IP infrastructure paves the way for a broader range of multimedia channels for reaching emergency services. Total conversation, including real-time text (RTT) and Next Generation eCall (NG eCall) will benefit from this shift, as they all require seamless end-to-end connectivity to IP networks. The transition to all-IP emergency communications is not optional. Technological developments and regulatory requirements make it a necessity.

Requirements set out in the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC), its supplementing Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/444, the European Accessibility Act (EAA) and recent amendments to the eCall regulatory framework are now providing the catalyst for transitioning PSAP infrastructure across Europe to be able to handle multimedia emergency communications based on IP technologies. Member States were required to submit roadmaps to the European Commission for the transition of their PSAP systems to packet-switched technologies by 5 December 2023.

As national authorities in Europe prepare for the inevitable transition, critical decisions need to be made regarding the most effective approach for each country taking into account the organisation of the emergency communications infrastructure and operations. A key consideration will be ensuring the continuity of existing legacy access methods until all public networks and PSAPs become IP-enabled.

The Emergency Services IP Network (ESInet) and Next Generation Core Services (NGCS), as described in ETSI Technical Specification (TS) 103 479, provides an optimal solution for handling both legacy voice and next-generation multimedia emergency communications simultaneously. Many European countries are using ETSI TS 103 479 as the blueprint for their plans.

This blog post aims to demystify the implementation, operation and regulation of ESInets and NGCS by providing a clear and straightforward explanation of the architecture and components described in TS 103 479 so that public authorities, public safety answering points (PSAPs), electronic communications networks and service providers can readily identify their respective roles and responsibilities in enabling IP-based emergency communications at the national level.

How does the ESInet and NGCS facilitate emergency communications?

The ESInet is a dedicated IP network specifically designed to securely connect individuals in emergency situations with PSAPs. It’s a crucial component of the Next Generation 112 (NG112[1]) architecture and serves as the platform for hosting the NGCS.

In simple terms, the ESInet provides the transport architecture that enables delivery of emergency communications to PSAPs while the NGCS provides security, discovery and the routing functionalities needed to ensure the emergency communications are delivered to the most appropriate PSAP.

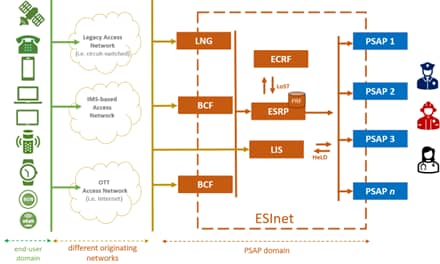

Along with the ESInet, the NGCS consist of the following core elements:

Border Control Function (BCF) – The point of interconnect between the public network and the ESInet. It provides a firewall and additional security layer for protecting the other core components. Emergency communications received at the BCF are forwarded to the ESRP.

Emergency Services Routing Proxy (ESRP) – With its policy routing functionality (PRF), the ESRP provides dynamic routing capabilities. Multiple rules can be evaluated in order to determine the most appropriate PSAP or the next “hop” en route to the most appropriate PSAP. The ESRP interacts with the ECRF and the LIS.

Emergency Call Routing Function (ECRF) – The ECRF is queried by the ESRP for information on which PSAP is responsible for a specific service type (e.g. police, fire or ambulance) at the caller’s specific location. This query is performed using the Location-to-Service-Translation (LoST) protocol. Depending on the complexity of the call handling model deployed in a given country, an ECRF may only be needed in order to interact with a Forest Guide[2] for interconnectivity between different countries.

Location Information Service (LIS) – The LIS provides location information for a specific entity (e.g. an end-user’s phone) using the HTTP-Enabled Location Delivery protocol (HELD).

Legacy Network Gateway (LNG) – A key component during migration, the LNG provides the interface between legacy circuit-switched networks and the ESInet.

Emergency communications originating on public networks (both mobile and fixed) are transited through an ESInet from different originating networks and are routed to the most appropriate PSAP using routing intelligence inside the ESInet provided by the NGCS.

Figure 1: Architecture and core elements for network-independent access to emergency services (compiled from description contained in TS 103 479)

Figure 1 above should be viewed through a logical rather than a physical lens. While the ESInet and NGCS can be implemented, operated and maintained by a single entity, it is possible to have several organisations involved and it is possible to provide at least some of this functionality “as a service” using cloud services.

As the routing responsibility resides inside the ESInet, the levels of availability, resilience and redundancy we expect from mission critical communications services must apply. This requires resource, expertise and a high-availability mindset for the operation and maintenance of the NGCS and the services they provide within ESInets. Until now, these have been core competencies of publicly available electronic communications networks and service providers alone.

Therefore, public authorities responsible for emergency communications need to consider whether to undertake to operate and maintain the ESInet and NGCS themselves or to outsource some, or all, of this responsibility to third parties. This is where it becomes essential to understand the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders at national level and what roles and responsibilities are expected of them during and after the migration to all-IP emergency communications.

Who is responsible for the ESInet and the NGCS within it?

This is the key question and, having had discussions with some Member State authorities, it is one that is being grappled with. Some say that they do not see the need for all components because they have a centralised emergency communications handling model[3]. In this case it is quite straightforward to specify a point at which all electronic communications networks and service providers originating emergency communications can send their traffic to.

Others see it as essential because they have a decentralised model[4] but are not sure who should be responsible for it or who should pay for it. The policy and routing rules might be set by public authorities but operation/implementation could be delegated to one or more electronic communications networks or service providers.

Regulators may ask who has the responsibility for “routing to the most appropriate PSAP” as defined in legislation? Is it the public network operators and service providers? Is it the operator of the ESInet? Is it a combination of both? This is important as it begs the question about regulatory reach. How far inside the ESInet should electronic communications regulation extend? The answer to that question is “it depends on who is doing what”.

NG112 Deployment Options

Option 1 – Contract with one or more commercial entities (e.g. network operators) – Responsibility is outsourced to an expert that provides installation maintenance, operations, monitoring and security as a managed service with infrastructure/services provided onsite, through cloud services or through a combination of both. It is advisable to keep scalability in mind using this approach as bandwidth and operational capacity may need to be increased to meet future needs. Also, an appropriate service level agreement would need to be in place that recognises the mission critical nature of the operation.

Option 2 – Do it yourself – Provides complete control over hardware/software and routing mechanisms. This facilitates faster response times for troubleshooting, root cause analysis and resolution. Cost may be a factor as there will be a need to be adequately resourced to provide a mission critical, high-availability 24×7 service. However, there may be some potential for resource and cost sharing if collaborated upon by several regions within a country.

Option 3 – A hybrid approach – A combination of 1 and 2 above which may provide scope for more options with respect to network redundancy/resilience using owned and outsourced parts of network. There is also the potential for resource and cost sharing if collaborated upon by several regions and the inhouse resource commitment may be reduced. With this option, the ESInet could be based on Option 2 with NGCS provided based on Option 1 or vice versa.

Status of next generation projects in Europe

Over the last number of years EENA has tracked plans and projects for NG112 implementation. Following submission to the European Commission of national roadmaps for upgrades and plans for fixed and mobile network migration, we expect an acceleration on projects in Europe in the next two to three years. Here is a brief summary of projects we do know about right now:

North Macedonia was the first European country to complete the transition to NG112.

Switzerland has also completed its transition to a solution that ensures IP-based emergency calling and the delivery of location information to PSAPs over IP.

Austria has implemented the DEC112 app. The platform and NGCS supporting DEC112 accords with TS 103 479.

Romania will complete its transition in 2024 in what is the most ambitious NG112 project in Europe to date. The Special Telecommunications Services in Romania is responsible for the implementation and operation of the ESInet and NGCS.

Portugal has also begun its transition to NG112 with a detailed focus on IP-based emergency calling and the delivery of location information to PSAPs using Session Initiation Protocol (SIP).

We understand that Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania and Sweden are in the tendering phase for their respective NG112 projects.

Want to learn more?

EENA published a document entitled “NG112 Implementation Steps” describing the key milestones that need to be met for an end-to-end NG112 implementation in accordance with TS 103 479.

Other recent publications which are relevant include documents on NG112 Testing, NG112 Forest Guide – ESInet Interconnection, IMS Packet Switched Emergency Communications & ESInet Interconnection and Next Generation eCall: Integration with an Emergency Services IP Network.

If you are thinking about starting your NG112 journey or you are already at the planning stage, EENA’s NG112 Education Programme may be for you. This programme is provided to stakeholders at national level, in confidence and in a workshop format. The programme provides further details on the topics discussed in this blogpost drawing on the experience from implementation projects in other countries from Europe and beyond. If your interest is piqued after reading this, please contact Freddie McBride ([email protected]) at EENA for more information.

[1] Next Generation 112 (NG112) is a term that is well known and commonly understood by many stakeholders in Europe. It refers to the implementation of IP-based emergency communications in accordance with ETSI TS 103 479.

[2] The main purpose of a Forest Guide is to interconnect the ESInets of the individual countries. It provides a pointer where additional information about the responsible ESInet can be found. This pointer can then be used to retrieve the technical endpoints for different services within the ESInet.

[3] Regardless of type of emergency communications or the location of the emergency caller, all emergency communications are delivered to a central Stage 1 PSAP. They still however need connectivity to Stage 2 PSAPs and route emergency communications based on location and/or type of emergency communication.

[4] The most appropriate PSAP is determined by the location of the caller and/or the type of emergency communications. For example, an eCall and a mobile-originated emergency voice call from the exact same area could be delivered to two different PSAPs.

Freddie McBride

- Freddie McBride#molongui-disabled-link

- Freddie McBride#molongui-disabled-link

- Freddie McBride#molongui-disabled-link

Share this blog post on: