The End Isn’t Nigh: Why there is Nothing to Fear About Public Warning Systems

- March 27, 2023

- Categories: Public warning

Scroll down social media or check the news in the UK, and you’ll no doubt hear that the UK has recently launched a new national emergency alerts system. The system aims to initially focus on the most serious severe weather-related events, with the ability to broadcast a message to 90% of mobile users within a relevant area in an emergency.

Yet rather than celebrate the introduction of significant public safety measure that has been proven to save lives, many media outlets and TV personalities have resorted to scaremongering with calls of nuclear attacks and alien invasions on the way. Fortunately for us, this is simply wrong – public warning systems are nothing to fear, and here is why.

Why do we need a public warning system?

In a rapidly-changing world, the need to quickly alert the population of ongoing crises or imminent threats becomes more necessary each day. Recent terrorist attacks, natural disasters and health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted the need for an efficient and reliable public warning system.

In a crisis – either man-made or natural – it is important to send information quickly and efficiently to the general population. For example, during a wildfire or a flood, it may be necessary to evacuate people living in a certain area. As approximately 90% of the general population have a smartphone, receiving a message on your phone is the most efficient and widespread way to give people instructions on what to do in an emergency.

In a life-threatening situation, time is key – the quicker you receive information on what to do, the quicker you can respond.

Who else has one?

Many countries already have a public warning system in place. It is mandatory in the EU for countries to have modern public warning systems (although implementation of these is still ongoing). In the USA, the Emergency Alert System (EAS) is a national public warning system that allows the president to address the nation within 10 minutes during a national emergency.

But my country doesn’t get hurricanes or natural disasters – why do we need a public warning system?

With the recent launching of a public warning system in the UK, many are asking why – considering the UK is widely seen to be a country with a mild climate with no extreme weather conditions, wildfires, hurricanes, earthquakes or other life-threatening natural disasters.

However, this is simply not true. The UK has regularly had natural disasters that required evacuation of people, heavy damage/danger to infrastructure and unfortunately deaths. The UK had severe wildfires in 2018 – burning over 9,000 acres of land. Floods and storms over the last 10 years have killed several and left millions without power, or with flooded homes. And yes, the UK does get the occasional hurricane and tornados – about 30 a year! In 2014 trials of the public warning system, the final project report found that ‘responders remain very keen to see the implementation of a national mobile alert system’ and that ‘the majority of people (85%) felt that a mobile alert system was a good idea.’

We’ve managed this long without it – why bother now?

In short, because public warning saves lives. Research from Outforia notes the UK has recorded 3,739 deaths caused by natural disasters since 2000. Around 434,413 have been affected in the UK by flooding and 61,088 by storms since 2000. Public warning not only saves lives through quicker and more efficient action in an emergency, but will save billions of pounds of damage to homes and livelihoods.

So how will it work?

The UK emergency alert system will work through a technology called cell broadcast. When people are present in an area (whether they are residents or visitors), this technology can broadcast a message to everyone connected to that cell tower – allowing the message to be targeted to a certain area.

Public authorities can use this technology to alert instantly (usually within 10 seconds) the population present near a disaster (it is possible to narrow it down to a few metres) and in a privacy-friendly manner.

What will I receive?

You will hear a loud beeping and vibration from your phone, and a message will pop up on the screen, similar to when you set an alarm clock using your phone. You have to acknowledge the message before you are able to use your phone for anything else.

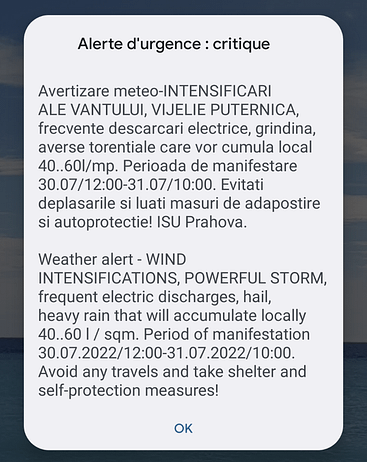

In a real emergency, it is likely that you will receive a short description of the emergency and instructions on what to do. Below, you can see an example from Romania’s public alert system:

What if my phone is out of battery or switched off?

You will likely receive the message in the same manner when you switch your phone back on, if the alert is still ongoing.

Is the government trying to track me or introduce spyware onto my phone?

Absolutely not.

The warnings are secure one-way communications which will be free to receive and put nobody’s personal data at risk. Only the government or emergency services will ever send the alerts, which will include the details of the area affected and provide instructions about how best to respond.

The alert is completely anonymised because it is sent to all phones in the area, rather than a dedicated list of handsets or specific numbers.

I want to turn it off!

There are very few reasons to. You will only ever receive an alert in a genuine emergency – where you are required to immediately act.

For particularly vulnerable people, such as domestic abuse survivors and those with learning disabilities, charities are offering specialised advice on how to manage alerts.

Where do I find out more?

At the European Emergency Number Association website – https://eena.org/our-work/eena-special-focus/public-warning/

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of EENA. Articles do not represent an endorsement by EENA of any organisation.

Amy Leete

- Amy Leete#molongui-disabled-link

- Amy Leete#molongui-disabled-link

- Amy Leete#molongui-disabled-link

- Amy Leete#molongui-disabled-link

Share this blog post on: